Ulula the Werewolf

Posted by Doris V. Sutherland on 24th Jul 2018

The Italy of the 1970s and ’80s was a hotbed of exploitation cinema. During this period, Italian directors, such as Lucio Fulci and Umberto Lenzi, built their careers around the most lurid screen epics. These films closely followed the coattails of Hollywood trends, but yet retained a spirit of gonzo invention. To pick just one case, George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) gave rise to Lucio Fulci’s zombie films such as Paura nella città dei morti viventi (City of the Living Dead), which freely blended their source material with a sense of Lovecraftian weirdness to create something unique.

All of this will be familiar to many English-speaking horror enthusiasts. What is less well-known in the Anglophone world, however, is that the same vibe can also be found in Italian comics of the era.

Known as fumetti, the comics of Italy have a rich tradition of exploitation titles that mix sex, violence, and the most gleefully pulpish of storytelling. These comics encompass a range of genres, including police procedural (La Poliziotta), swashbuckler (Moschettiera), and even fairy tale (Fata Turchina). Like their film counterparts, they borrow liberally from American pop culture: Karzan is a sexualised Tarzan parody, for example, while 44 Magnum is clearly derived from Magnum P. I. But once again, like their cinematic counterparts, they come across less as crude knock-offs and more like some kind of bizarre pop art.

Of all the exploitation fumetti, I am most attracted to the horror series. The American comics of the 1990s saw a crop of sexy, supernatural “bad girls” such as Lady Death, Purgatori, and Chastity, but Italy got there years beforehand: in fumetti we find the vampire girls Zora and Sukia, the devil girl Belzeba, and the Frankenstein-like Cimiteria.

One of the various fumetti conceived along these lines is Ulula, a title published by Edifumetto that made its debut in 1981. I have tried to scrape together hard information on its background, but with little luck. The comic itself does not credit any creators, and data regarding its publication is scanty. I have scoured second-hand issues listed for sale on Italian websites, and as far as I can tell the series lasted for thirty-six issues. In addition, issues 21 and 33 of a series called Supplemento appear to contain bumper-sized Ulula stories entitled “Buona Carne in Scatola” and “I Depravati di Manila,” while the first seven issues of Ulula were collected in a 1989 edition of Fumetti Record.

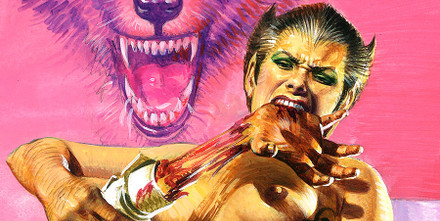

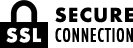

Ulula’s covers often depict the title character in a strange costume—a sort of one-piece, midriff-bearing swimsuit, sometimes with a cape attached. It seems safe to say Ulula owes a debt to the American anti-heroine Vampirella, who wears a similar skimpy red number.But Ulula—whose name means “howling”—does not sport Vampirella’s trademark bat motif. Her hair is styled to suggest a pair of wolfish ears, while her choker has two claws dangling from it. She is an example of a fairly uncommon breed: a sexy werewolf woman.

Today, we do not tend to associate werewolves with femininity, let alone physically attractive femininity. Cinematic werewolves have been portrayed as grotesque creatures from the genre’s beginning in The Werewolf of London (1935) and The Wolf Man (1941); this reached a height in the 1980s, when films such as An American Werewolf in London emphasised the visceral body-horror implications of the transformation from human to wolf. More recently, the likes of True Blood and Twilight have cast werewolves as earthy, conventionally masculine counterparts to refined and effete vampires.

But things were once very different. In the literature of nineteenth-century Britain, the favoured variety of werewolf was a beautiful—even ethereal—woman who acted as a temptress. This character type owes something to the widespread folk tale motif of the animal bride, variations on which include swan maidens, frog princesses, and—yes—wolf women.

Perhaps the ur-example of the Victorian werewolf temptresses is the White Wolf of the Hartz Mountains, who turned up in a chapter of Captain Frederick Marryat’s 1839 novel The Phantom Ship. Similar werewolves who followed her lead include Ravina in Sir Gilbert Campbell’s “The White Wolf of Kostopchin” (1889), Lilith in Count Eric Stenbock’s genuinely weird “The Other Side: A Breton Legend” (1893), and White Fell in Clemence Housman’s allegorical “The Were-Wolf” (1896). These women all have their brutal sides, but they are still essentially beautiful, as summarised by Housman’s description of White Fell:

She was a maiden, tall and very fair. The fashion of her dress was strange, half masculine, yet not unwomanly. A fine fur tunic, reaching but little below the knee, was all the skirt she wore; below were the cross-bound shoes and leggings that a hunter wears. A white fur cap was set low upon the brows, and from its edge strips of fur fell lappet-wise about her shoulders; two of these at her entrance had been drawn forward and crossed about her throat, but now, loosened and thrust back, left unhidden long plaits of fair hair that lay forward on shoulder and breast, down to the ivory-studded girdle where the axe gleamed.

In more recent decades, however, female werewolves have been less common. They have their place, certainly: Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing and the film Ginger Snaps both associate lycanthropy with menstruation, for example, while the likes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Being Human have included werewolf women amongst their ensemble casts. But contemporary lycanthropy, by and large, remains something of a boy’s club.

The reason for this is not hard to guess. Even in horror, women are generally expected to be conventionally attractive: just compare the Bride of Frankenstein with her male counterpart. The rending hides and grotesque distortions of the Hollywood werewolf—a world away from the fairy tale creatures described by Victorians—is hard to square with traditional feminine good looks.

A werewolf woman who is not only attractive but sexy is an even harder sell. Admittedly, one 1976 Italian film was released in English as Naked Werewolf Woman, but it is hard to imagine raincoat-clad punters queuing up for a film with such a name; unsurprisingly, the movie is better known simply as Werewolf Woman.

So, Ulula perhaps did not have the odds in her favour. When she made her debut in a story entitled “La Lupa Manara” (which translates as “The Female Werewolf” and, maybe coincidentally, is the original Italian title of Naked Werewolf Woman) how did her comic present itself to the fumetti-buying public…?

This is a strange cover, to be sure. If we rule out the possibility of Ulula being aimed at a very specific audience of paraphiliacs, then we are left with two possibilities. One is that the cover artist attempted to showcase the concepts of “sexy girl” and “scary werewolf” at the same time with little regard as to whether or not the result actually worked in either respect.

This is a strange cover, to be sure. If we rule out the possibility of Ulula being aimed at a very specific audience of paraphiliacs, then we are left with two possibilities. One is that the cover artist attempted to showcase the concepts of “sexy girl” and “scary werewolf” at the same time with little regard as to whether or not the result actually worked in either respect.

The other, perhaps less likely but nonetheless more interesting possibility is that the scene is deliberately surreal. It is almost as though the artist is saying to the prospective buyer, “you want sexy women? Well, we’ve got a sexy woman for you… but she’s not like any sexy woman you’ve seen before.”

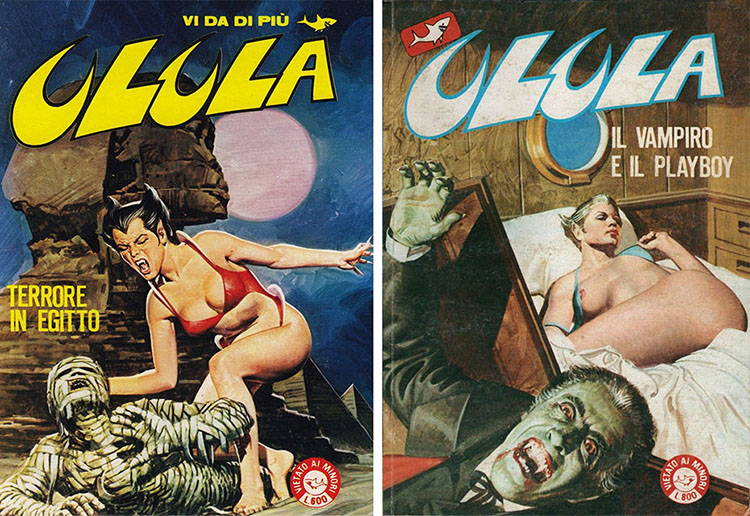

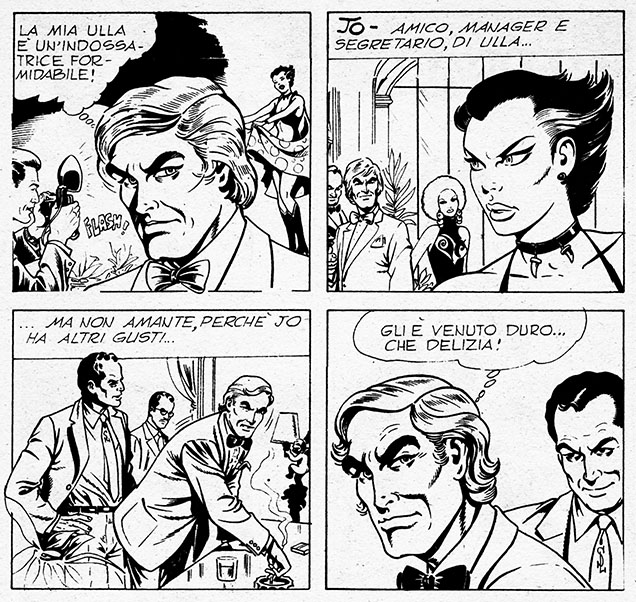

The story introduces its anti-heroine working as a model, strutting her stuff before an eager crowd in the swimsuit beloved by cover artists. Significantly, her name is one letter short: for the time being, she is simply Ulla.

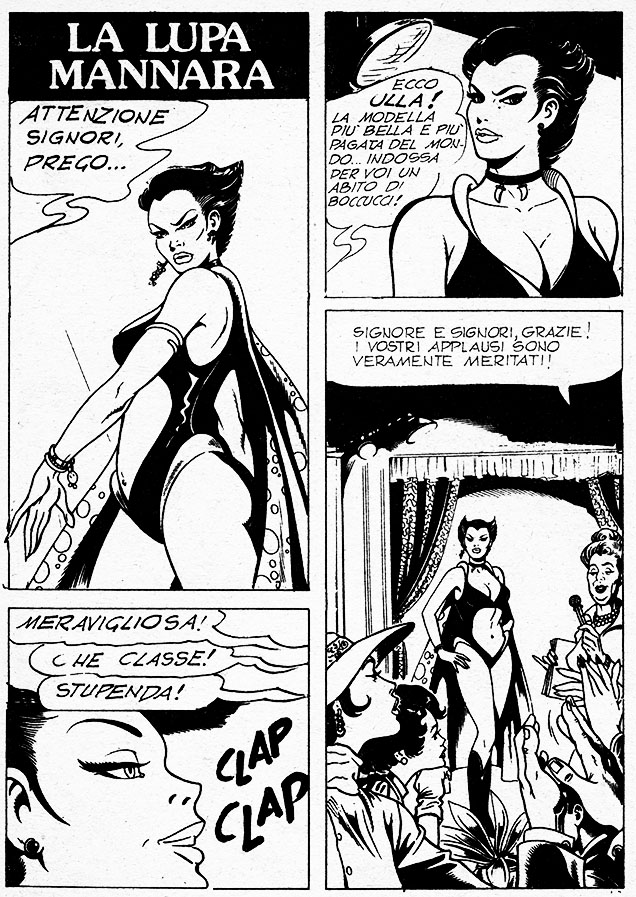

The next major character to turn up is a handsome fellow named Jo. A narrative caption identifies him as “friend, manager and secretary to Ulla … but not a lover, because Jo has other tastes.” To demonstrate this point, Jo arranges a date with another man. While Ulla proceeds to strip, shower and pleasure herself, the two men engage in anal sex.

Still frisky, Ulla calls room service and immediately seduces the waiter. At first, she expresses a degree of anxiety: it is only half an hour before midnight. The waiter suspects that she has to return to her husband by then; Ulla denies that she is married and begins fellating the man before he can ask any further questions.

The comic does not scrimp here, delivering an explicit sex scene that takes up just over three pages. The dialogue contains a notable element of racial fetishisation: Ulla regards the black waiter as a “stupendo mulatto,” while he refers to her as “bella troiona bianca.”

On a panel-by-panel basis, Ulla’s naked form is shown more than those of the men, but this is largely because she is the central character. The truth is that the idea of the male gaze—or even the gynophilic gaze—simply does not figure in Ulula. The heroine’s mounds and the waiter’s erect penis are depicted in the same loving terms, apparently on the assumption that the readership will find both subjects equally stimulating.

As the post-coital pair lie in bed, the clock strikes midnight and Ulla transforms beneath the full moon: “Ulla is gone … now there is Ulula”, proclaims a caption. The process turns out to be rather less thorough than depicted on the cover, however, simply giving her claws, fangs and a bestial scowl. On the sliding scale between human and wolf, Ulula stays fairly close to the former.

Ulula proceeds to kill the waiter by biting his throat. Before this, however, she makes the curious decision to tear off and eat his penis.

When the topic of sexual violence in horror films is brought up, concerns about misogyny are usually not far behind. And yet, if we look at how the motif of genital mutilation is used in the genre, we can see that horror cinema has shown quite a fascination with violation of the male member. As early as 1932, Tod Browning intended to imply the castration of a male villain in his film Freaks, although the idea was ultimately left out. Since then, I Spit on your Grave (1978), Cannibal Holocaust (1979), Night of the Demon (1980), Don’t Open Till Christmas (1984), Bad Karma (1991), and others have all depicted men having their knobs chopped off.

In the case of Ulula, the scene does not quite make logical sense: I am unaware of any species of predator that eats its prey genital-first. But perhaps the visual pun was too hard to resist. After all, two of the earlier panels showed Ulla eating that man’s cock in a less literal manner.

After Ulula transforms back into a human and realises her crime (“This curse haunts me! Sigh! Sigh!”) Jo arrives in time to help her dispose of the body. The entire story up until this point turns out to have been an in medias res prologue, and the comic now divulges to the anti-heroine’s origin:

It happened five years ago, in January, in the Black Forest … Ulla was the guest of a maternal uncle, a famous specialist in blood diseases: Count Wilfred von Hagen …

Ulla is shown crashing her car while on her way to visit her uncle. The Count happens to live in a stock Gothic castle: “The castle of my uncle is really chic, like Dracula,” muses Ulla before her accident. Meanwhile, Wilfred himself is surrounded by the kind of nondescript apparatus beloved of comic book and b-movie mad scientists.

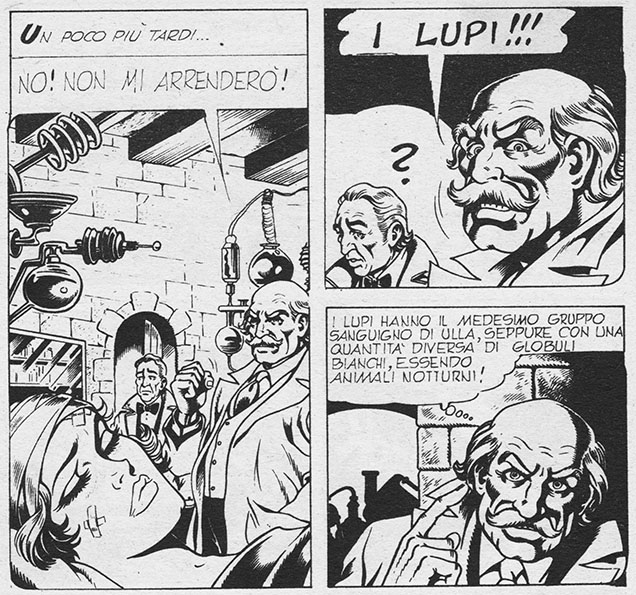

Confronted with the unconscious and bleeding body of his niece, Wilfred decides to give her a blood transfusion. Alas, with no suitable human donors in the immediate vicinity, the scientist’s only option is to use blood from one of his test animals—specifically, a wolf.

Ulla recovers and appears to be in good health. However, her uncle shows a decidedly shady side. When she kisses him on the cheek in gratitude, he thinks to himself, “Troietta! Me lo fa anche tirare!” (this means something along the lines of “Slut! She’s turning me on!”)

The twist should not surprise us too much, as Wilfred appears to have been conducting a TUBE during the blood transfusion:

Wilfred agrees to let Ulla celebrate her recovery by throwing a party, but he is still troubled by impure thoughts. “I have to stay away from her,” he thinks to himself. “So sensual that she excites me, but she is the daughter of my sister! Maybe it is because I have not been to bed with a woman for a long time … I’ll take advantage of the party to invite Countess Ilona … she’s always ready to give it to me!”

The party does not go entirely to plan. After a brief altercation with a sleazy young man who gropes her backside and gets a slap on the face as a reward (“I find the boys unbearable”, she thinks to herself), Ulla comes across her uncle having sex with the nubile young Countess Ilona.

Then we get the next twist. In a thought bubble, Ulla reveals that she, too, has incestuous fantasies: “Uncle is the most beautiful of the boys that I masturbated to in high school!”

Up until now Ulla—who feels remorse for the murders carried out by her werewolf-self—has been a sympathetic character. With the revelation that she has erotic designs on her uncle, however, she turns out to have a thoroughly sordid streak. She is far from the innocent victim that we may have expected.

Distracted by her incestuous voyeurism, Ulla fails to notice the full moon in the sky as the midnight hour draws close…

The issue takes the opportunity to end on a cliffhanger. In its treatment of the werewolf theme, the story sticks to convention. The portrayal of a lycanthrope as a tragic protagonist, who is forced against their will to become a murderous monster, is entirely consistent with the formula established in the Universal films.

The pseudo-scientific origin for Ulula’s affliction, while unusual, is not unique. In the post-war years, monster movies drifted away from the old Gothic ghouls in favour of aliens, radioactive mutants, and the like. While werewolves and vampires would still turn up, their traits were often explained away using the kind of pseudo-scientific business previously associated with the Frankenstein and Invisible Man films; examples of this include the hypnotically-created lycanthrope in I Was A Teenage Werewolf (1957) and the portrayal of vampirism as a blood infection in 1945’s House of Dracula (which, like Ulula, uses a blood transfusion as a plot device).

The trend did not last long. With the honourable exception of Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend, these mid-century technofantasy vampires now seem terribly dated, while the fantasy figures portrayed by Max Schreck and Bela Lugosi live on in our imaginations. That Ulula revived this approach decades after it had run its course suggests that the comic’s creators were rather careless in their cribbings: they were interested less in the folkloric resonance of the werewolf concept and more in the visceral potential of the genre.

So, what does Ulula add to the werewolf formula? Well, the simple answer is sex. Hammer’s Carmilla trilogy, Jean Rollin’s arthouse horror, and countless Italian and Spanish exploitation romps had combined Gothic fantasy with sexual titillation, but Ulula and its fumetti kindred took things a step further. This is material that would not be seen onscreen outside of hardcore porn.

The combination of sex and violence in the comic is uncomfortable, but surely that is the point of horror?

Horror fiction has long drawn upon sexual themes. The slasher films of the 1980s and ’90s established the vaguely puritanical cliché in which people who have sex are doomed to be murdered. Almost a century beforehand, Bram Stoker invoked rape imagery when describing Dracula’s attack on Mina Harker. Going back still further, we find legends of such supernatural sex fiends as the succubus and incubus.

Of course, not all horror writers have been keen on eroticism. M. R. James explicitly avoided sex in his works, not out of moral concerns, but simply because he found sex too boring a subject to be used in a ghost story. But yet, generations of storytellers and audiences have found sex and horror an irresistible combination.

What should we make of that? Is Ulula a contemptuous piece of exploitation, a harmless bit of derivative nonsense, or an enjoyably brash pulp adventure? Could we even make a case for it as being—at least in some respects—a progressive work, thanks to its gay portrayal and subversion of the male gaze?

Well, that is something that I will leave up to the reader to decide. “La Lupa Mannara” is not a particularly sophisticated comic, but it is at least an honest one. It promises a no-holds-barred orgy of sex and gore, and that is what it delivers.

Republished with permission from womenwriteaboutcomics.com

To discover more about the world of “sexy fumetti” check out the following books Sex and Horror: The Art of Alessandro Biffignandi and Sex and Horror: The Art of Emanuele Taglietti.